Jamshid Jambulov’s journey from growing up in southern Uzbekistan to being accepted into a paid Research Fellowship at Harvard Medical School began with applying to the FLEX program. As a 16-year-old, he sought support from several teachers to help him write his essay because he felt his English wasn’t good enough. However, their suggestions didn’t capture his true feelings, so he wrote “from his heart.”

Jamshid Jambulov’s journey from growing up in southern Uzbekistan to being accepted into a paid Research Fellowship at Harvard Medical School began with applying to the FLEX program. As a 16-year-old, he sought support from several teachers to help him write his essay because he felt his English wasn’t good enough. However, their suggestions didn’t capture his true feelings, so he wrote “from his heart.”

The day the FLEX finalists were to be notified happened to be on Jamshid’s birthday, April 23. He hadn’t heard anything throughout the day, so he went out that evening. When he returned, family and friends had gathered at his house to celebrate his birthday. However, no one had told him until late into the evening he had received the scholarship; they assumed he had known! After the celebration, as people started to leave around 1 a.m., they unknowingly shared the good news with him as they congratulated him on the success. It was the ultimate surprise party.

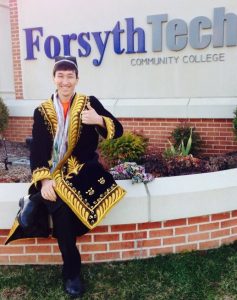

While on FLEX, Jamshid was a prolific volunteer, earning President Obama’s volunteer  service award for his time working on different community projects while going to high school. After he returned to Uzbekistan, he taught English in Qarshi for three years, and established a small English Language Center with his friends, but his dream of returning to the U.S. never left him. He stayed in touch with his American host family in North Carolina, who suggested that he enter a community college near them.

service award for his time working on different community projects while going to high school. After he returned to Uzbekistan, he taught English in Qarshi for three years, and established a small English Language Center with his friends, but his dream of returning to the U.S. never left him. He stayed in touch with his American host family in North Carolina, who suggested that he enter a community college near them.

Jamshid first considered becoming a diplomat, but he felt politics wasn’t right for him. His host father, a local North Carolina artist, suggested he should study medicine. But he was not interested in medicine at all, as he did not like science classes while in school. Becoming a doctor seemed daunting – but Jamshid liked the idea of a challenge, so after being accepted into a U.S. program, he enrolled in Anatomy and Physiology. In addition to his studies, Jamshid started to volunteer at a local hospital in his host family’s hometown, helping patients and their loved ones navigate the building, and he soon began making friends and earning the respect of others at the hospital.

Volunteers weren’t allowed into the operating room, but Jamshid was curious and persistent. He needed to have a background check and some other supporting documents, but eventually he was allowed to observe surgeries. He was told he must be completely sterile, dress in scrubs, stay six feet away from the surgical table, and absolutely not distract anyone. For someone who had never been in an operating room in his entire life – even in Uzbekistan – this experience felt like entering a new world.

One of the doctors sitting beside the patient, the anesthesiologist, saw him in the far corner of the room and asked, “Who’s that guy?” A nurse said, “He’s a student and wants to learn.” After a long silence, the doctor said, “Come over here,” which meant that “six-feet rule” no longer applied to Jamshid. He was happy to be able to come close to the patient, observe, and ask questions from the doctors. Then, the surgeon came in and performed open-heart surgery. When he cut the chest open, he told Jamshid to come over and stand at his right shoulder. Jamshid watched as the surgeon gently lifted the beating heart in his hands – and that’s when Jamshid knew he wanted to be a cardiac surgeon.

One of the doctors sitting beside the patient, the anesthesiologist, saw him in the far corner of the room and asked, “Who’s that guy?” A nurse said, “He’s a student and wants to learn.” After a long silence, the doctor said, “Come over here,” which meant that “six-feet rule” no longer applied to Jamshid. He was happy to be able to come close to the patient, observe, and ask questions from the doctors. Then, the surgeon came in and performed open-heart surgery. When he cut the chest open, he told Jamshid to come over and stand at his right shoulder. Jamshid watched as the surgeon gently lifted the beating heart in his hands – and that’s when Jamshid knew he wanted to be a cardiac surgeon.

The next morning, Jamshid found an opossum that had fallen into his host family’s swimming pool and drowned. He laughs at the memory, “So what did I do? I attempted my first surgery!”

After two years of applying, Jamshid was later accepted into a program studying Interventional Cardiac and Vascular systems. He stayed beyond the clinical hours, as evenings were busier for heart attack patients, thus more intense and more interesting. Doctors and nurses were very nice and friendly to teach him important skills and allow him to be independent. He ultimately completed the program with honors.

Sadly, five days before starting his new job, Jamshid learned that his father in Uzbekistan was ill. He had been sick for some time, but his parents didn’t want Jamshid to be worried, or be distracted from his board examinations. When he learned of his father’s illness, he immediately wanted to come home, but didn’t have the money. When he finally found some money, he received a call that his father passed away. He wanted to give up  everything, come home, and be with his family. But his Dad’s wish was that he must study hard, become a doctor, and when the time comes, give back to his community. Nothing would stop him from keeping his promise to his father.

everything, come home, and be with his family. But his Dad’s wish was that he must study hard, become a doctor, and when the time comes, give back to his community. Nothing would stop him from keeping his promise to his father.

Jamshid threw himself into his new job, working extra hours to keep his mind off the loss of his father. His department treated over 6,500 patients in one year. “I saw many people in bad shape, and wanted to make sure they would recover, and be able to reunite with their families,” Jamshid said, “I would think about my father, and knew he would be proud.”

Jamshid needed to return to college to receive his BS degree, and recalled hearing from instructors that if he wanted to get into medical school, doing research would help to stand out among other applicants. He began searching online for programs and applied for 40.

That winter break, his American host father felt ill. On Christmas Eve, he drove to the hospital, where he learned he had late-stage cancer. He died within two weeks of diagnosis. Jamshid was despondent.

Then, rejection letters started arriving. Three, four, five per week. Sometimes he’d receive two rejection letters from the same school by mistake. Soon, 37 of 40 programs had sent him rejection letters. He was offered interviews too, but luck was not on his side. Then come rejection number 38. Then 39.

On February 1, Jamshid received an email from his very last application. He opened the email, which began as, “Dear Jamshid Jambulov…” He laughs, “All 39 rejections started as “Dear Jamshid Jambulov…”” He stood up and backed away from the computer, unable to scroll down. He paced the room, then returned to the screen. Then he read, “Welcome to Harvard Medical School.”

On February 1, Jamshid received an email from his very last application. He opened the email, which began as, “Dear Jamshid Jambulov…” He laughs, “All 39 rejections started as “Dear Jamshid Jambulov…”” He stood up and backed away from the computer, unable to scroll down. He paced the room, then returned to the screen. Then he read, “Welcome to Harvard Medical School.”

Jamshid talks about how lucky he is, his grandparents’ life as farmers, and how his father was the first in his family to go to college. However, throughout his entire life, Jamshid has seen great adversity and challenges, but he faced it with a positive attitude, hard work, and a sense of humor.

Later this month, Jamshid will enter Harvard Medical School as a paid research fellow. He kept his promise to his father and followed his heart.